Thursday, October 22, 2009

1981 Hunger Strike: Chain of Command

“Rusty Nail” at Slugger O’Toole

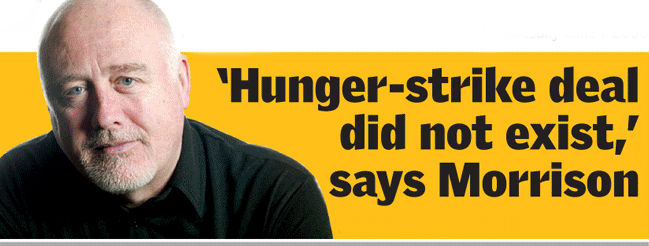

Lots of ground to cover today, with a lot of detail. In today’s Irish News, former hunger striker Bernard Fox says the matter should be laid to rest out of respect for the families, while Richard O’Rawe and Tony O’Hara seek answers.

This post jumps off a quote referenced in one of today’s articles, and expands the background.

Richard O’Rawe’s article references a quote from Nor Meekly Serve My Time. This book, first published in 1994 and reissued in 2006 for the 25th anniversary of the hunger strike, was complied by Brian Campbell, and edited by Campbell, Laurence McKeown and Felim O’Hagan. It’s an oral history of the H-Block Struggle as told by the prisoners and as such is a valuable historical resource. For those interested in the current hunger strike issue, it contains some nuggets which put the current and shifting Morrison narrative under further pressure. Where it is a real problem, in that context, is that these are the words of people like McFarlane and McKeown; their earlier record contradicts the line being claimed today, and supports the alternative narrative. The two can’t both be right – either they were lying then or they are lying now. What is worse, from the perspective of those defending the contemporary Morrison narrative, is that the book itself can be seen as evidence of collusion in the cover-up by what it has left out. In this regard, the book is a no-win for that position – but the historical record stands.

The business starts on page 198-199 (2006 ed.) with Bik McFarlane describing the background to the ICJP involvement around the 4th of July. The key quote from that section:

“Speculation began to mount in the media and rose to fever pitch when the ICJP was granted permission to visit the hunger strikers. Expectations among our people outside were high – surely this was a clear sign that the pressure had finally forced the British to open negotiations and implement a solution?”

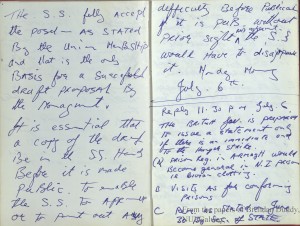

On the next page (200) McFarlane explains the chain of command surrounding negotiations:

“It was Saturday 4 July when the delegation arrived at the prison hospital to speak with the hunger strikers. The Brits stipulated that I could not be present, so the first meeting took place while I remained in my cell. I was pretty annoyed at being excluded because we had already agreed amongst ourselves that negotiations about a settlement would not take place without me being there to represent the views of all the POWs. In fact, our original position, as established by Bobby Sands, that negotiations would only take place in the presence of three advisors (Gerry Adams, Danny Morrison and myself), had not been dispensed with. However, some of the hunger strikers felt that, since they weren’t actually negotiating a settlement, but only hearing what the ICJP had to say, then to possibly jeopardise the meeting by insisting on my presence would, in their opinion, have been foolhardy. But we had allowed a wedge to be driven in which would be difficult to remove. The hunger strikers did inform the delegation that, in the event of a settlement being negotiated or agreed upon, I would have to be consulted, and they urged the ICJP to seek a meeting with me as soon as possible. ”

Contrast this with his statement to Brian Rowan, 4 June, 2009, about meeting with the hunger strikers after they had met with Danny Morrison:

“We went through it step by step,” he said. “The hunger strikers themselves said: OK the Brits are prepared to do business — possibly, but what is detailed, or what has been outlined here isn’t enough to conclude the hunger strike.

“And they said to me, what do I think?

“And I said I concur with your analysis — fair enough — but you need to make your minds up,” he continued.”

What was McFarlane’s role, and how much power did the hunger strikers themselves actually have? Was he merely a ‘consultant’ or was he the one issuing orders? As O/C, he most certainly would have had to have been consulted. But what was the flow of information? How much information did the hunger strikers have about what was being done in their name? Clearly, it was McFarlane who was in charge, not the hunger strikers, and what we see in the tension between these two accounts is the shifting of the onus of responsibility by McFarlane from himself onto the hunger strikers.

CHAIN OF COMMAND

Given that the hunger strikers were never fully informed, and were – in McFarlane’s own words – unable to negotiate on their own behalf, the idea that they and they alone were calling the shots is a nonsense. That is how it should have gone: the O/C would inform the prisoners of the details of negotiations and consult with them, and would be speaking for the prisoners; those representing the Army on the outside would have as their duty to inform the O/C of all that was being said and to be doing as the prisoners wished. Any negotiations and offers from the British, such as what came via the Mountain Climber, would also have to be made known to the Army.

Ruairí Ó Brádaigh is explaining this when he says the Army Council was unaware of any offer coming from the British. Ó Brádaigh’s comments in the Irish News very clearly follow along traditional Army lines.

First and foremost, the Army Council could not order prisoners onto hunger strike. Once a prisoner or prisoners made the decision to go on hunger strike, the prisoners themselves were to be in control – it was they who were to make the decisions about any settlements. However, while the Army Council could not order a prisoner onto hunger strike, if it would help the prisoners they could order them off it (this is what Father Faul wanted Adams to do when he visited the hunger strikers at the end of July).

Standard structure meant that the O/C inside the prison was empowered to negotiate with the prison governor or screws. However, if negotiations were conducted at the level of the British government, that was to be handled by the Army Council on the outside. The A/C representative was to keep the prisoners informed of the negotiations, including any offers being made, so that the prisoners could decide what they were going to do. In this aspect the Army Council’s role would best be seen as a facilitator, not a dictator. They were to keep the prisoners fully informed of negotiations being conducted on their behalf, and to take instructions from the prisoners.

In addition to this, the IRA constitution had its own mandate the Council had to follow; no business could be conducted without a quorum of 4; any settlement or offer the British made, the full Council had to be made aware of, as well as the fact that the British were in direct talks with Army representatives.

What Ó Brádaigh is making very clear is that this was not the case. What was being done by Adams, McGuinness, Morrison and the others was not sanctioned by the Council; the Council did not know. Just like the prisoners, they were told nothing.

There was no quorum as mandated by the IRA constitution; what was being done was being done outside Army structures. The prisoners weren’t in control of their hunger strike, the flow of information was not happening as it should have done. Those representing the Army on the outside were not following the wishes of the prisoners as expressed by the O/C, but rather the other way around. The O/C was dictating to the prisoners what those on the outside were ordering him. Those on the outside were running rogue and not keeping their Army colleagues abreast of their negotiations with the British – nor of their plans to radically change political strategy, of which this hunger strike was a major part of implementing.

This back-to-front order is reinforced in a comm from McFarlane to Adams. He is speaking of the events of the 5th of July; Morrison had been in to see the hunger strikers in the morning and then met with McFarlane; the ICJP came in that evening and spent four hours with the hunger strikers before meeting with McFarlane after midnight:

“Meeting terminated about midnight and Bishop O’Mahoney and J. Connolly paid me a short visit just to let me know the crack. Since then I haven’t been to see anyone except Lorny and Mick Devine on the way back to the block this morning. Requests to see hunger strikers and O/Cs have not been answered at all…I’m instructing Lorny to tell hunger strikers (if they are called together) not to talk to anyone till they get their hands on me. OK?”

The same comm very explicitly describes how he discussed the ICJP offer with the hunger strikers – not the Mountain Climber one – and the line he instructed them to take.

On page 205, Laurence McKeown describes Danny Morrison’s visit to the hunger strikers:

“Danny told us the history of their contact with the ICJP and also mentioned other contacts with the British Foreign Office (none of the communication between the Republican Movement and the British government at this time has ever been admitted to by the latter). We outlined our position to him and told him we had heard nothing so far to make us believe there was resolution to the stailc in sight. The ICJP would, however, be returning that evening. We split up and Danny went to see Bik who hadn’t been allowed to be present with us during out meeting. I was happy with what had taken place. It seemed there was movement. Why else would the NIO agree to Danny’s visit with Bik and us? I felt we were in a strong position.”

The hunger strikers were told nothing, none of the details of the offer from the Mountain Climber – merely that contact had been made. The only indication of any sort of movement that the hunger strikers had was Morrison’s presence. They were told nothing.

This also shows the chain of command in action; Morrison only told the hunger strikers that there was contact; he told McFarlane the details of the offer.

McFarlane elaborates, on page 208:

“While they [the ICJP] were hopping back and forth between Stormont and the Kesh in supposed negotiations with Alison, the British government had secretly opened a link to the IRA and begun negotiations to attempt to resolve the issue. My first knowledge of this came when I had been summoned to the prison hospital that Sunday morning only to be confronted by Danny Morrison. I was completely flabbergasted at seeing him there; my mind was racing through all sorts of computations. It transpired that the Brits had agreed to allow him into the Kesh to consult with us and to explain the nature of the contact which had been established. There was definitely an air of optimism gripping me, but I was urged to be cautious, as it was possible that nothing would emerge to satisfy our demands.”

McFarlane, 4 June, 2009 interview with Rowan:

“Something was going down,” McFarlane said.

“And I said to Richard (O’Rawe) this is amazing, this is a huge opportunity and I feel there’s a potential here (in the Mountain Climber process) to end this.”

On page 210, McFarlane again:

“Back in the block, I waited for news that would end the nightmare, but the comms I received from the Army Council showed the Brits still hadn’t gone beyond the position we had agreed and had reaffirmed on Sunday in the hospital. Then on Wednesday we received the heartbreaking news that Joe had died early that morning. It was more than tragic because I had been holding out hope that this was the chance we had longed for.”

Richard O’Rawe, Blanketmen, page 184:

“Bik and I were shattered. The possibility that the Council might reject the proposals had never entered into our calculations. We were convinced that we had achieved a great victory and that the republican movement could present the deal as a momentous triumph; now it appeared that our analysis and optimism had been both flawed and premature.”

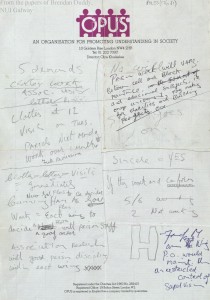

10pm comm from McFarlane to Adams:

“I don’t know if you’ve thought on this line, but I have been thinking that if we don’t pull this off and Joe dies then the RA are going to come under some bad stick from all quarters. Everyone is crying the place down that a settlement is there and those Commission chappies are convinced that they have breached Brit principles. Anyway we’ll sit tight and see what comes…”

THATCHER’S OFFERS

Thatcher continued her pursuit of Adams’ acceptance of her offer throughout July; between the 18th and 19th, during the ‘frank statement’ exchanges, she sent him a draft of a speech she was to give in Canada that would have announced the end of the hunger strike. From Adams’ biography Before the Dawn, page 303:

“During our contact in the course of the hunger strike, her government representatives approached us in advance of a world leaders’ conference in Canada at which she was due to speak on 21 July. “The Prime Minister,” they said, “would like to announce at the conference that the hunger strike has ended.” They outlined the support we had and the support we didn’t have, and then went on to tell us, “This is what the Prime Minister is prepared to say.” They fed us a draft of the speech that Thatcher was going to deliver in Toronto, and there was no doubt that they were prepared to take amendments to her text from us if it had been possible to come to some sort of resolution at that time.”

In an interview in Canada on the 21st, Thatcher was sending a very clear message to Adams when responding to a question about where things would go next:

“I just hope that those people on hunger strike will come off it. It is futile. It can do them no good at all. It is for them or for the people who are influencing them to go on hunger strike. It is for them to get off. It is they who are causing the deaths of these people.”

McFarlane’s 22 July comm to Adams discussing this is very stark (Ten Men Dead, 329-330):

“Comrade Mor, I got your comm today. Quite a revelation I must say. I lay on my bed for a couple of hours, trying to weigh up everything. Almost dashed out of my cell once or twice. I even toyed with the idea that their ‘very frank statement’ was a master-stroke linked to a super brink tactic. It was then that I wised up and started looking to the future (immediate and distant) and began moving to a positive line.

Firstly I’d like to say I believe you have done a terrific job in handling this situation and if we can take the opposition’s ‘frank statement’ as 100% (which it does appear to be) then in itself it is quite some feat, i.e., extraordinary such an admission from them. Then again I suppose it is something we have all known already (or at least suspected).

Anyway, to be going on, I fully agree with the two options you outlined. It is either a settlement or it isn’t. No room for half measures and meaningless cosmetic exercises. Better be straight about it and just come out and say sin e – no more!!

Now, to maintain position and forge ahead, it looks like a costly venture indeed. However, after careful consideration of the overall situation I believe it would be wrong to capitulate. We took a decision and committed ourselves to hunger strike action. Our losses have been heavy – that I realize only too well. Yet I feel the part we have played in forwarding the liberation struggle has been great. Terrific gains have been made and the Brits are losing by the day. The sacrifice called for is the ultimate and men have made it heroically. Many others are, I believe, committed to hunger strike action to achieve a final settlement. I realize the stakes are very high – the Brits also know what capitulation means for them. Hence their entrenched position. Anyway, the way I see it is that we are fighting a war and by choice we have placed ourselves in the front line.

I still feel we should maintain this position and fight on in current fashion. It is we who are on top of the situation and we who are the stronger. Therefore we maintain. In the immediate this means that Doc and Kevin will forfeit their lives and as you say the others on hunger strike could well follow. I feel we must continue until we achieve a settlement, or until circumstances force us into a position where no choice would be left but to capitulate.

I don’t believe the latter would arise. I do feel we can break the Brits. But again, as you say, what is the price to be? Well, Cara, I think it’s a matter of setting our sights firmly on target and shooting straight ahead. It’s rough, brutal, ruthless and a lot of other things as well, but we are fighting a war and we must accept that front-line troops are more susceptible to casualities than anyone. We will just have to steel ourselves to bear the worst. I hope and pray we are right.”

At this point, Adams was rejecting the Thatcher offer because “Association during leisure hours was not enough and in addition they would need specific assurances as to what they would be allowed to receive in parcels”. (Ten Men Dead, page 325) The offer from Thatcher contained 4 of the 5 demands and she was also promising to remove the prison governor, Stanley Hilditch, who was replaced when the hunger strike dwindled to an end in October (McFarlane met with the new prison governor, Willy Kerr, on 21th October).

ADAMS MEETS HUNGER STRIKERS

All of this is to preface Adams’ meeting with the hunger strikers on 29 July. We are meant to believe, according to the current Morrison narrative, that the hunger strikers were fully informed at all points about all details and were the ones who were calling the shots. Yet the evidence clearly contradicts this, both in terms of the information the hunger strikers were privy to, and what the chain of command in effect was. The hunger strikers were told next to nothing; they were certainly never given the full details of the Thatcher offers. Any information they were given about what Thatcher was offering was shaded in terms of what line the hunger strikers were to take. When the prison leadership was briefed on the early July Mountain Climber offer, they accepted it, and they were over-ruled by Adams and his committee. McFarlane was at great pains to keep everyone in line, and on the conveyor belt of self-sacrifice, beyond the point where they had broken the Brits and had won the demands they were striking for.

Laurence McKeown describes the meeting with Adams in Nor Meekly Serve My Time. Key quotes:

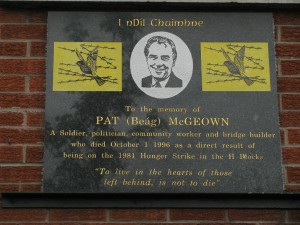

“One evening during lock-up the AG came to tell us that Gerry Adams, Owen Carron, and Seamus Ruddy would be coming to visit us in about one hour’s time. It was something out of the blue. There had been no talk about it nor had any of us requested such a meeting. I had been lying in bed but now I got up to pace the floor – an old habit of mine formed during the Blanket. I thought this must be a positive sign. If Gerry Adams and Owen Carron were coming, it must mean some approach had been made to them by the Brits.” (page 234)

“Those of us who did meet – Pat Beag, Big Tom, Paddy, Red Mick, Matt and myself – were in good form, curious about what was happening and speculating on what could be behind it all. The fact that Seamus Ruddy, an IRSP spokesperson, was also coming with Adams and Carron added to the speculation that a possible deal had been worked out with all involved. ” (234-235)

“Gerry said that, when asked, he readily agreed to visit us and give us an appraisal of the situation and how he saw our position in relation to the possibility of the Brits conceding our demands. It was a grim picture. There were no ifs or buts. Really he was spelling out for us what we in a sense knew but didn’t like to think through. The Brits had already allowed six men to die and they would likely allow more to die. Certainly there was no movement to indicate that they desired a speedy resolution to the protest.” (235)

Did Adams not tell the hunger strikers of the offer being made only a few days before? Didn’t the hunger strikers know about the ‘frank exchange’ that had taken place only a week before? Didn’t they know what had gone on with the Mountain Climber offer? McKeown writes as if they knew nothing of any of this going into the meeting, and what is worse, as he tells it, they were not told of any of it during the meeting with Adams.

McKeown goes on, describing Adams’ brief visit with Kieran Doherty:

“Gerry explained the reason for their visit just as he had done with us. Doc was told that what it would mean for him if he continued on hunger strike was that he would be dead within a few days. Doc said he was very much aware of that, but if our demands were not granted, then that is what would happen. He knew what he was doing and what he believed in. On their way out of his cell Doc’s parents met and spoke with Gerry, Bik and the others. They asked what the situation was and Gerry said he had just told all the stailceoiri, including Kieran, that there was no deal on the table from the Brits, no movement of any sort and if the stalic continued, Doc would most likely be dead within a few days. They just listened and nodded, more or less resigned to the fact that they would be watching their son die any day now.” (236)

Adams lied.

Appendix:

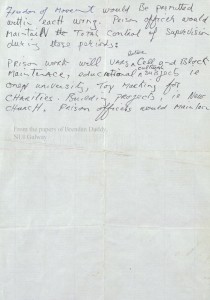

The July offer from Thatcher:

I. extend to all male prisoners in Northern Ireland the clothing regime at present available to female prisoners in Armagh Prison (i.e. subject to the prison governor’s approval);

II. make available to all prisoners in Northern Ireland the allowance of letters, parcels and visits at present available to conforming prisoners;

III. allow the restoration of forfeited remission at the discretion of the responsible disciplinary authority, as indicated in my statement of 30 June, which hitherto has meant the restoration of up to one-fifth of remission lost subject to a satisfactory period of good behaviour;

IV. ensure that a substantial part of the work will consist of domestic tasks inside and outside the wings necessary for servicing of the prison (such as cleaning and in the laundries and kitchens), constructive work, e.g. on building projects or making toys for charitable bodies, and study for Open University or other courses. The prison authorities will be responsible for supervision. The aim of the authorities will be that prisoners should do the kinds of work for which they are suited, but this will not always be possible and the authorities will retain responsibility for decisions about allocation.

3. Little advance is possible on association. It will be permitted within each wing, under supervision of the prison staff.

4. Protesting prisoners have been segregated from the rest. Other prisoners are not segregated by religious or any other affiliation. If there were no protest the only reason for segregating some prisoners from others would be the judgment of the prison authorities, not the prisoners, that this was the best way to avoid trouble between groups.

Regarding the IRA Army Council’s role

Excerpted from Anthony McIntyre’s interview with Richard O’Rawe (May 16, 2006)

Q: There are many memorable pages in your book. It is a moving account of how naked men for years defied a vicious and brutalising prison management working for the British government to brand the mark of the criminal on republicanism. But the real point of controversy is your assertion that the Army Council stopped a deal being reached that would have delivered to the prisoners the substance of the five demands. Army Council people of the time seem to dispute this. Ruairi O’Bradaigh, for example, is on record as saying that the council did no such thing although he does state that your claims must be explored further. It seems clear that he suspects you are right in what you say but wrong in whose door you lay the blame at. What have you to say to this?

A: At the time we had no reason to believe we were dealing with any body other than the Army Council of the IRA. What reason was there to think otherwise?

Q: And not a sub-committee specifically tasked with running the hunger strike?

A: Whether they called it a sub-committee or not, we were of the view that everything went to the Army Council. Nobody led us to believe any different. Did you think any different?

Q: At the time, no.

A: We all felt it was the Council. Brownie was representing the Council and he wrote the comms. Why would we think we were dealing with anything less than the Council when he was the man communicating with us?

Q: You might not wish to say it but for the purpose of the reader – and this has been publicly documented in copious quantities – Brownie is Gerry Adams, who was a member of the Army Council and the IRA adjutant general during the hunger strike.

A: I have nothing to add to that.

Q: But do you still hold to the view, despite the protests from O’Bradaigh, that the Council actually prevented a satisfactory outcome being reached?

A: No, I do not. Army Council was the general term I used to describe the decision makers on the outside handling the hunger strike. I was not privy to Army Council deliberations. But I believed they were the only people who had the authority to manage the hunger strike from the outside. So it seemed safe then to presume that when we received a comm from Brownie it was from the Army Council as a collective.

Q: But what has happened to lead you to change your mind and accept that the Council may have been by-passed on this matter by Gerry Adams?

A: I have since found out that people on the Army Council at the time have, after my book came out, rejected my thesis and refused to accept that the Council had directed the prisoners to refuse the offer.

Q: Bypassing the Council as a means to shafting it and ultimately getting his own way would seem to be a trait of Gerry Adams. Do you believe then that the bulk of the Council did not approve blocking an end to the hunger strike before Joe McDonnell died?

A: Absolutely. The sub committee managed and monitored the hunger strike. Given that comms were coming in two and three times a day it is simply not possible to believe that the Council could have been kept informed of all the developments. Could the Council even have met regularly during that turbulent period?

Q: Could they not be covering for their own role?

A: I have not spoken to any of the council of the day. But those that have claim that they appeared genuinely shocked that my book should implicate them. And they do allow for the possibility that the wool was pulled over their eyes by the sub-committee handling the strike.

Q: So what do you think did happen?

A: As I said in my book, Adams was at the top of the pyramid. He sent the comms in. He read the comms that came out. He talked to the Mountain Climber. As I said earlier, we know that he, and possibly the clique around him, decided to reject the second offer, at least, without telling Bik what was in it. Nobody knows the hunger strike like Adams knows it. And yet he is maintaining the silence of the mouse, the odd squeak from him when confronted.

Here’s what he said in relation to the Mountain Climber in the RTE Hunger strikes documentary,

‘There had been a contact which the British had activated. It became known as the Mountain Climber. Basically, I didn’t learn this until after the hunger strike ended.’

He didn’t learn what? About the contact and the offers, or the Mountain Climber euphemism? If he’s saying he didn’t know about the offers, then why did he show the offer to the Father Crilly and Hugh Logue in Andersonstown on 6 July 1981? And if he’s saying he didn’t know of the Mountain Climber euphemism, I’d refer your readers to Bik’s comm to Adams on pages 301-302, Ten Men Dead, where Bik tells Brownie, who is Adams, that Morrison had told the hunger strikers about the Mountain Climber: ‘Pennies has already informed them of “Mountain Climber” angle’ So he knew about the Mountain Climber euphemism, and he knew of the offers. As a defensive strategy, this lurking in the shadows, this proceeding through ambiguity, can only work for so long. At some point academics and investigative journalists are going to ask the searching questions and Gerry Adams is not going to be up to them.

Q: Are you now suggesting that Adams may have withheld crucial details from the Army Council?

A: I don’t know the procedural detail of the relationship between Adams and the Army Council. What I do know is that my account of events is absolutely spot on. You said yourself on RTE on Tuesday that there was independent verification of the conversation between myself and Bik McFarlane.

Q: Indeed. I think you realise there is a bit more than that. As you know I have enormous time for Bik. It goes back to the days before the blanket. But I can only state what I uncovered. I am not saying that it is conclusive. These things can always be contested. But it certainly shades the debate your way. If Morrison and Gibney continue to mislead people that there is no evidence supporting your claim from that wing on H3 I can always allow prominent journalists and academics to access what is there and arrive at whatever conclusions they feel appropriate. That should settle matters and cause a few red faces to boot. We know how devious and unscrupulous these people have been in their handling of this. They simply did not reckon on what would fall the way of the Blanket. Nor did I for that matter. A blunder on their part.

A: If the Army Council say they received no comm from us accepting the deal, and also say that they sent in no word telling us effectively to refuse the deal, then I think the only plausible explanation is that those who sent in the ‘instruction’ to reject the Mountain Climber’s offer were doing so without the knowledge or approval of the Army Council.

Q: When you say ‘those’ you presumably mean Adams and Liam Og who was also sending in comms coming to the prison leadership?

A: Yes.

Q: Liam Og has been identified by Denis O’Hearn, author of the biography of Bobby Sands, as Tom Hartley. It appears that Hartley was privy to every comm between the leadership and the prisoners.

A: That would be the case.

Q: How can we be sure that Adams rather than Liam Og was responsible for withholding information from the Army Council?

A: Because, while we might not know the procedural detail, Adams had a relationship with the Army Council that was vastly different from Liam Og. You point out that this is well recorded in public.

Q: If you absolve the Army Council of the day, as a collective, of responsibility for sabotaging a conclusion to the hunger strike that would have saved the lives of six men, who do you hold responsible?

A: Maggie Thatcher had the responsibility for bringing this all to an end.

Q: But given that she made an offer, which would have brought it to an end, and which was sabotaged, who then on the republican side, if not the Council, was responsible?

A: You are trying to tie me down.

Q: I should not have to. You should be telling us directly if as you say you believe in our right to know.

A: Let’s put it like this. The iron lady was not so steely at the end. She wanted a way out. The Army Council, I now believe, as a collective were kept in the dark about developments. The sub-committee ran the hunger strike. Draw your own conclusions from the facts.

Sourced from Slugger O’Toole

![Pol35_0166_0001 Send on 5 of July Clothes = after lunch Tomorrow and before the the afternoon visit as a man is given his clothes He clears out his own cell pending the resolution of the work issue which will be worked out [garbled] as soon as the clothes are and no later than 1 month. Visits = [garbled] on Tuesday. Hunger strikers + some others H.S. to end 4 hrs after clothes + work has been resolved.](http://www.longkesh.info/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Pol35_0166_0001-300x228.jpg)

Ever since the former IRA volunteer and Blanket-man Richard O’Rawe, published his book, Blanket-men: An untold Story of the H-Block Hunger Strike, (2005) there has been an ongoing and increasingly bitter debate amongst Irish Republicans; over the truth of O’Rawe’s claim that the Thatcher government had offered a viable deal, which could have ended the hunger strike after the death of Patsy O’Hara, the fourth hunger striker to die. The importance of this matter cannot be overstated, for if proved true, O’Rawe’s claim removes the shibboleth which has since become established fact, i e the hunger strikers were in charge of their own destiny. As Bobby Sands and his fellow H/S were disciplined revolutionary soldiers, this is something which should never have held water.

Ever since the former IRA volunteer and Blanket-man Richard O’Rawe, published his book, Blanket-men: An untold Story of the H-Block Hunger Strike, (2005) there has been an ongoing and increasingly bitter debate amongst Irish Republicans; over the truth of O’Rawe’s claim that the Thatcher government had offered a viable deal, which could have ended the hunger strike after the death of Patsy O’Hara, the fourth hunger striker to die. The importance of this matter cannot be overstated, for if proved true, O’Rawe’s claim removes the shibboleth which has since become established fact, i e the hunger strikers were in charge of their own destiny. As Bobby Sands and his fellow H/S were disciplined revolutionary soldiers, this is something which should never have held water.  Stature of ten men unassailed

Stature of ten men unassailed

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.