Honour of those who died needs explanation

THE HUNGER STRIKE

By Hugh Logue of the Irish Commission for Justice and Peace

28/09/09

The image of those eight hunger strikers for me has never dimmed. Clothed predominantly in the white attire of hospital, the weakest sitting at a table, water jugs and mugs in hand, the strongest seated on higher tables, or standing behind.

That scene has stayed with me over the last 28 years and will remain imprinted in my brain as long as I live. They had been brought together as a group from their hospital beds to meet us in the canteen of Long Kesh.

Bright articulate young men, some reserved and quiet spoken, others defiant and inquisitive, eyes accentuated, all in various stages of physical decline, eager to live, ready to die. Like their image, respect for them has never dimmed.

I met them as part of the Irish Commission for Justice and Peace (ICJP) as we sought to explore the possibility of squaring their five demands by stretching the British prison regime to a more enlightened, humane, innovative and educationally positive system. The Irish government gave us their full support.

After much coming and going, a best offer was finalised involving new rights on clothes, work, recreation/education, remission and association.

The hunger strikers were positive but cautious, wanting the wider view of their comrades. The prisoners on July 4 issued a statement indicating that a settlement along such lines should be considered.

We were meeting with the relatives and some H-block committee members when the prisoners’ statement reached us. With good reason, the meeting finished with the view that the choreography of concluding the Hunger Strike without further loss of life was being set in place.

Next day we met again with the relatives and on this occasion Sinn Fein representatives were present. The relatives made clear their wish to go for the ICJP-brokered offer.

A senior IRA representative left the meeting early, without saying where he was going, and went in to see the hunger strikers.

When we later visited the hunger strikers that night, their mood had hardened but a number of them clearly indicated that what was on offer was acceptable.

Eventually all agreed that if the British government sent a delegate into the prison and read out the offer it would be accepted.

This condition, we were told, had been demanded as a minimum by the IRA representative who had visited them. Double dealing on the earlier botched hunger strike was given as the reason for this demand.

We went back to the British and it was agreed that an envoy would visit the hunger strikers to read out the offer. As we all know, the British prevaricated and Joe Mc Donnell tragically died before any visit was made, triggering a whole new scenario.

The ICJP next day railed against the British government for its unpardonable complacency and indicted its utterly callous conduct.

That indictment remains.

Four years ago – when I reviewed Blanketmen [by Richard O’Rawe] – I asked that a sane debate take place on its principal assertions, instead of the vilification of its author.

I also suggested that were the Mountain Climber, the British and the republican leadership to spell out what they knew, it would be possible to reach informed conclusions.

The British, via the Freedom of Information Act, have now put new material into the public domain. Mountain Climber has now stated that he passed the British offer to his IRA interlocutor. In what form did the offer come?

Was British secretary of state [Humphrey] Atkins able to sign off if he got an affirmative reply from the IRA? It now appears he was.

Did those in the republican leadership understand that? Parallel Republican writing that Margaret Thatcher wished a settlement suggests they did.

This exchange was at least a day before the hunger strikers were told to demand, via the ICJP, verification from the British authorities.

If the IRA had the British offer , why were the hunger strikers being put through a ritual? The hunger strikers, on the instruction of the IRA, were demanding that the ICJP deliver the British to deliver an offer statement. And the British, whilst agreeing to deliver the statement, apparently were waiting on the okay from the IRA before delivering the statement to the hunger strikers that they had already delivered to the IRA.

And all the while, a hunger striker was slipping in and out of consciousness, edging closer to death. Too grotesque to contemplate. But it happened. Why? Truly, in the name, honour and dignity of the hunger strikers, explanation and clarification is needed.

This is not said for any reason other than that I genuinely do not know for sure, to this day, where the motivation of others lay.

I do know that we in the ICJP had an honourable resolution that would have saved the lives of six hunger strikers and that it was acceptable to the hunger strikers.

It appears from the British statement, given to the IRA via the Mountain Climber, that the British were ready to stand over all that had been agreed with the ICJP.

But were they only ready to go public on it if they got thumbs up from the Republican leadership?

Was there procrastination on the IRA side where a clear affirmative response would have sealed the deal and saved those lives? Was there a rejection?

Did the IRA genuinely overplay their hand believing that once the British were into dialogue more could be extracted?

The high regard that many serious political leaders now have for the republican leadership relates to their focus on ‘the long game’. Did ‘the long game’ focus come into play on this occasion?

Republican leadership has been assiduous in having its tale of ‘the struggle’ committed to history, but the Hunger Strike has been given a wide berth.

Some years ago, as the 20th anniversary of the Hunger Strike approached, I was told by a senior republican that the reason for staying away from the Hunger Strike was ‘because of the range of views, feelings and passions it could arouse within the movement – not all of them positive.’

He was right about that, but whatever those views feelings and passions, it is time for truth to shine.

Sourced from The Irish News

Stature of ten men unassailed

Stature of ten men unassailed

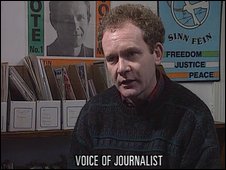

Sinn Fein talked tactics while hunger strikers died

Sinn Fein talked tactics while hunger strikers died

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.

It has withstood the blows of a million years, and will do so to the end.